Ecosystem restoration is a key element of repairing damage to the planet and working towards a sustainable future. In theory, ecosystem restoration is simple. You simply regrow damaged or lost habitat. Saying this and doing it however, are two very different things. Ecosystem restoration is still a very new, often poorly understood science. It is very difficult to know all the elements that make an ecosystem, so replicating these elements in restoration is difficult.

A critical element of restoring ecosystems is therefore monitoring restoration efforts, so researchers can learn what is and isn’t working. Professor Eric Gorgens and his team from the Universidade Federal dos Vales do Jequitinhonha e Mucuri (UFVJM) are testing how drones might be able to help this process.

Ecosystem restoration from mining in Brazil

Eric and a colleague preparing to map with a drone. Source: Eric Gorgens

Usually, restoration success from these mines is tracked through fieldwork every two to three years. Eric and his team are trying to make this process easier and faster by applying drones to the problem.

“To use drones is faster because I will take maybe one day to measure four, five plots. And with drones, in the same day, I can fly maybe hundreds of hectares in the one day. So I get access to a lot of information faster and with a very interesting resolution,” Eric said.

But the data that drones collect is often different to what can be collected with fieldwork. Before drones can be applied to monitor restoration success, Eric and his team need to work out what variables to measure and how to measure them.

What drones can measure

Vegetation structure and complexity is one variable Eric thinks could provide valuable insight into ecosystem restoration success.

“When you have a more complex vegetation, you used to have layers of vegetation in different heights and and species, and different species will occupy different niches of the structure,” Eric said.

“If the recovery process goes fine, you will have, along the time, the vegetation will become more complex, more structured.”

Vegetation structure is not simple to measure through ground-based fieldwork. However it can be easily quantified from the 3D point cloud generated from drone mapping images. 3D point clouds, as the name suggests, show the three-dimensional structure of the area a drone maps.

“So with drones, especially using the 3D cloud, we can try to understand a little bit how this structuration is going on in that region, in that place, we are recovering,” Eric said.

Another variable Eric and his team are testing is the ability of drones to distinguish different vegetation types. Bare ground, grass and trees each reflect different amounts of red, green, blue and near-infrared light. A drone with an RGB or multispectral sensor can measure these different spectral signatures, allowing Eric to quantify the area covered by different types of vegetation. Less bare ground and increasing tree coverage are indicators of restoration success.

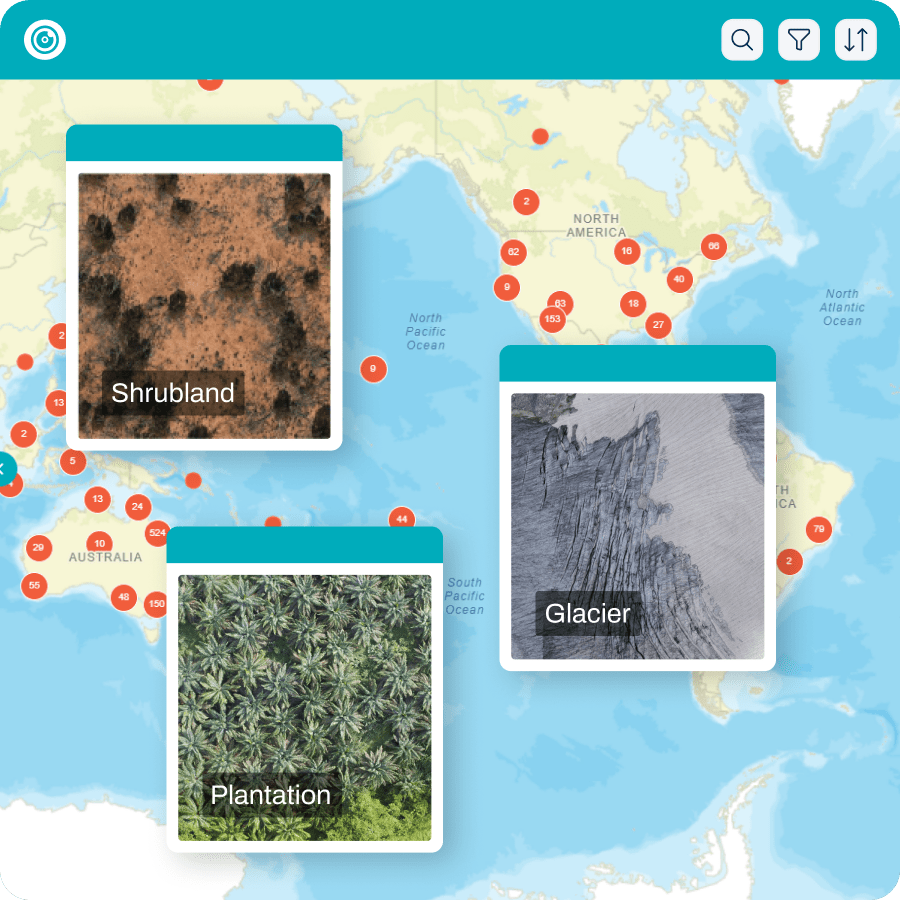

Examples of the types of vegetation Eric and his team are monitoring. Source: Eric Gorgens

What about satellites?

Not only do drones help capture new, helpful data that aren’t easy to collect with fieldwork, they also offer advantages over the data available from satellite images.

“[Using drones] there is the possibility to get more details about the objects that we are imaging. For example, the resolution usually is much higher in drones,” Eric said.

“We have the possibility of generating 3D clouds. This is also interesting, especially relating to the vertical structure. And we also have more control of the visits of the areas. For example, I can visit every month at a specific time, so I have more control about when I will acquire the images that I want to monitor for the region,” he added.

What still needs to be figured out?

For all the benefits that drones can offer, there are still some challenges with using drones for monitoring ecosystem restoration efforts. In part, what drones can achieve is restricted by what resources researchers can access. For example, the infrared band of the electromagnetic spectrum is very useful when trying to distinguish different vegetation types. But most standard drone cameras only record in the red, green and blue bands. Sensors which record in the infrared are more expensive, so they’re less accessible.

Using only RGB sensors, Eric found it hard to identify and distinguish plant species from the imagery.

“We have some limitations to identify trees. For example, we have a very high diversity of species living in the same area, and it’s very hard sometimes to differentiate species based on image,” Eric said.

“This [access to multispectral sensors] is a challenge for monitoring tropics, especially. In subtropics, we have very few species, so sometimes you have just four and five species in an area. But here we will have 200-300 species in the same area, so it’s much more complex. It’s much more difficult to monitor tropics,” he said.

There is also the challenge of figuring out where the data collected by drones can’t compensate for field data.

“I don’t have some metrics that I used to have in the field, for example, [tree trunk] diameters,” Eric said.

“Sometimes I cannot recognise the species based on drones based on images, so we have a trade off,” he said.

“But the research is exactly working on that. How can we reduce the trade off and match and mesh up techniques, monitoring techniques to complement the fragilities of the other? So we can try to combine different techniques to get the most of each one”

Manage and share your data on GeoNadir

Do you work with drone mapping data? GeoNadir is a free platform dedicated to the storage, management and sharing of drone mapping data from all over the world. We’ll even automatically turn your raw images into an orthomosaic!

Don’t have any data of your own to upload? No worries! There’s plenty to see and learn from the datasets users like Eric, have already uploaded.