Intermittently Closed and Open Lakes and Lagoons (or ICOLLs for short) are a common ecosystem near many coastal towns. But despite being on many people’s back doorstep, local communities often misunderstand them. This makes managing these systems tricky, especially when what the environment needs isn’t what the community wants.

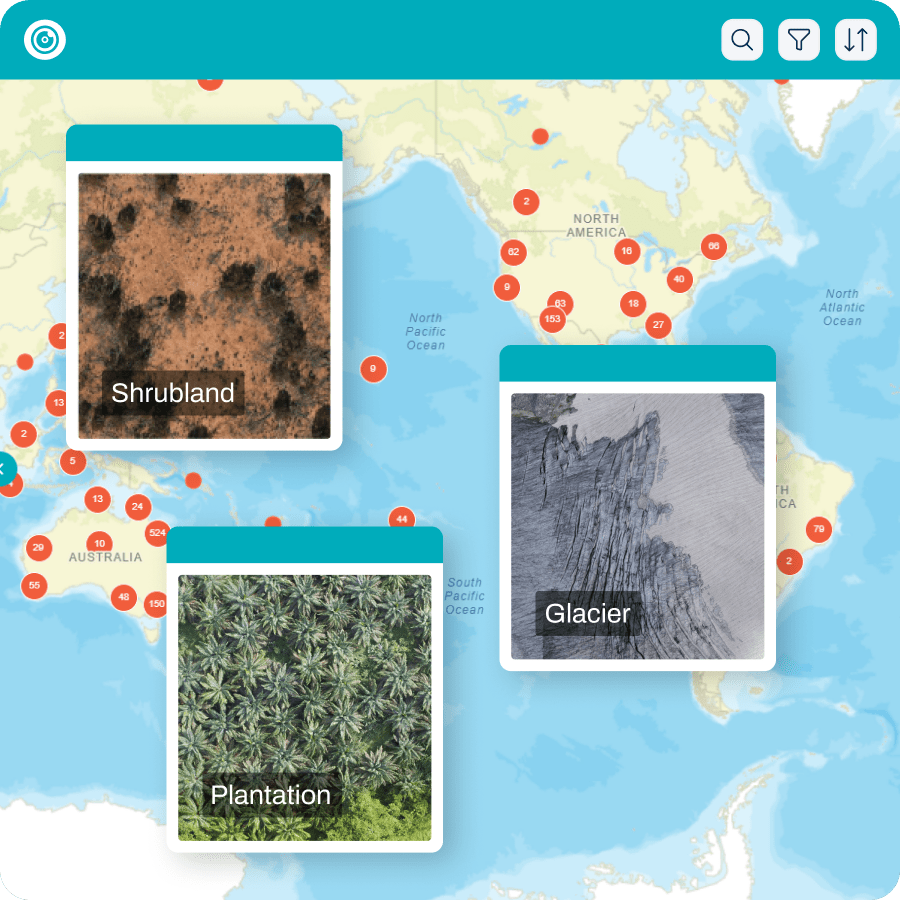

Stories from Above is about learning more from the awesome drone datasets that users have uploaded to GeoNadir. Often, that means talking about the cool and innovative ways that drones are helping collect data and solve environmental problems. But equally important is the way that some of this incredible drone imagery can spark discussions about environmental issues. Especially those that don’t always get a lot of attention, like ICOLLs.

So, let’s talk about ICOLLs. The processes that form them, where the conflict with communities comes from, and why it’s so important to manage them properly.

What are ICOLLs?

Satellite

Satellite

Drone

Drone

Drone imagery of Coila Lake after being artificially opened and satellite imagery of the lake when it was closed.

Source: Simon Hill (view the collection on GeoNadir)

An ICOLL is a kind of estuary, where freshwater from rivers and lakes inland runs out to meet the sea. Unlike your usual estuary however, ICOLLs aren’t always open to the ocean. Sometimes, a sand berm forms across their entrance. This effectively closes these lakes and lagoons to the ocean, sometimes for years at a time.

Whether the sand berm is forming, breaking down, or even there at all, varies depending on conditions. Waves are constantly trying to build up the sand berm across the entrance, while the freshwater is constantly trying to wash that sand away. These push and pull processes result in a natural, irregular cycle of ICOLLs opening and closing. The biodiversity of ICOLLs has adapted to these cycles.

But many of these ICOLLs are near people. And the natural cycles of these systems don’t always match a community’s needs.

Why do communities prefer open ICOLLs ?

You may have heard on the Australian news in early March that Lake Tabourie and the Shoalhaven River in NSW had been artificially opened. Heavy rainfall meant there was a high chance these closed ICOLLs would flood nearby low-lying infrastructure before they opened naturally. Pre-emptively opening the entrances reduced flood risk for these communities.

Reducing flood risk is the main reason ICOLLs are artificially opened. Beyond flood triggers, the management plans for most ICOLLs don’t permit artificial openings. However, this wasn’t always the case in the past. Many communities still perceive open ICOLLs as being healthier, or better than closed ones.

Closed ICOLLs can seem like they have poor water quality. This is often due to the muddy, brown colour they develop with the build-up of organic matter. This can be worse in dry years, when the ICOLL isn’t getting fresh flow from upstream. Communities sometimes believe water quality would improve if they artificially open the ICOLL to the ocean. Some people also feel that open ICOLLs are better for fish stocks.

The result is communities sometimes pressuring local governments to artificially open ICOLLs more often. Sometimes people will even try to illegally open the entrance themselves. But opening these systems artificially has the potential to cause a lot of environmental harm.

What’s the natural cycle of an ICOLL?

Every ICOLL has it’s own unique cycle of opening and closing. Some ICOLLs will naturally open more often than others and some will rarely open at all. Generally, how often and when an ICOLL opens depends on rainfall.

ICOLLs close in drier periods, when there is little or no freshwater inflow from upstream. Waves can then build the sand berm up faster than the freshwater can wash it away and the ICOLL closes.

ICOLLs open during wet periods, especially floods, where the sudden influx of water causes the ICOLL to overtop the sand berm. When this happens, the water quickly breaks through the berm, scouring a channel through to the ocean. As the water drops, the waves begin to build up the sand berm again and the cycle starts over.

ICOLLs that have more water flowing from upstream tend to be open more often, while ICOLLs with only small freshwater flows tend to be closed more often.

Why can artificially opening ICOLLs cause problems?

Ecosystems

Lots of biodiversity has adapted to, and relies on, the natural opening and closing cycle of ICOLLs. Wetlands and aquatic vegetation like seagrass rely on a certain level of lake water, inundation, and salinity to survive. Regularly opening lakes below their natural breakout level can cause a drop in water levels. This strands some areas and the amount of habitat available for fish and other marine creatures shrinks. More frequently open ICOLLs also generally have higher salinity since tides flush them more regularly. A switch from being a closed, largely freshwater ecosystem to an artificially maintained, open, salty ecosystem can change the whole biodiversity of an ICOLL.

Water quality

When there isn’t a lot of fresh water flowing in, artificial openings can also cause a phenomenon called ‘decanting’. This is when only the surface water of an ICOLL drains when the entrance is opened. When decanting happens, the only water left in the lake is the extremely low oxygen (hypoxic) bottom waters. This leftover hypoxic water isn’t suitable for a lot of animals and can cause large scale fish kills.

While fish kills can still happen with natural openings, natural openings are generally associated with flooding. This mixes the surface water with the hypoxic water and flushes the ICOLL. It makes it more likely the water will remain healthy for the fish and other creatures that live there. The result is that artificial openings can actually make the water quality worse than if the ICOLL remained closed.

Fish

Apart from fish kills from poor water quality, there’s no evidence that opening ICOLLs helps fish populations. In fact, opening ICOLLs to the ocean can mean fish are more exposed to predators and less successful at reproducing. Artificial openings can also interrupt natural cycles that fish have developed to benefit from natural openings of ICOLLs. Openings at the wrong time can lead to young fish ending up at sea before they are strong enough to survive.

Finding the balance

The science now shows that opening ICOLLs outside of their natural patterns does more harm than good. However, when communities don’t understand how the ecosystem naturally behaves, it can lead to a conflict between the environmental needs and social needs of a community.

Luckily most local governments in Australia now have management plans in place to make sure that ICOLLs are only opened to reduce flooding during rainfall events. Using flood triggers makes sure that artificial openings only happen when a natural opening would have happened anyway. This minimises the potential negative ecological impacts from opening ICOLLs. It is also illegal to open ICOLLs without permission, although people still attempt it from time to time.

How can drones help?

When ICOLLs open, naturally or artificially, the shape of the local coastline changes quickly as a new channel is established. Drones allow researchers to map the shore prior, during and after these opening events to learn how sand is being transported and deposited.

Although satellite imagery can help researchers learn about this, opening events usually happen at the same time as rainfall. The entrance to the ICOLL is therefore often obscured by clouds. Drones allow more flexible and frequent coverage of ICOLLs even in cloudy weather, helping researchers track changes over time.

Drones can also provide high resolution elevation data using Structure from Motion (SfM) photogrammetry. This can help researchers understand changes in the height of the sand berm and the profile of the surrounding beach in response to waves or waterflow.

How can I help?

Telling the stories of these ecosystems helps people learn more about them, the threats they face and how people can help. But right now, the stories of so many ecosystems mapped by drones are trapped in storage on a hard drive where no one can hear them. By uploading your drone images to GeoNadir, you can help others learn from your work, and hear your ecosystem’s story. If you think you’ve captured something really interesting or important we’d love to hear from you!

Otherwise, consider exploring some of the other amazing datasets that people have already uploaded here, or read more about the stories behind the collections through the Stories from Above blog.

Happy flying!