People often ask me what inspired me to create GeoNadir. To be honest, first and foremost it was selfish intention to make my life easier. Since 2013 I have amassed a huge amount of drone mapping data, and I’ve always had the problem of how to store, process, and share it in a simple workflow. I was drowning in data, with no easy way to even visualise all the data together, let alone find what I needed. Also, lots of other researchers and students around the world ask to use my data. I wanted them to be able to easily explore my holdings and access what they need.

Over the past two years, we’ve brought GeoNadir to life. Right now I am in an extremely remote location, and GeoNadir is doing its job to perfection and making my life easier.

Life on Carrie Bow Cay, Belize

The Carrie Bow Cay field station by The Smithsonian Institution is just magic. A tiny blip in the Carribean off the coast of Belize, it astounds me that it holds such an incredible, well equipped field station. The island is just 100 m long! And I cannot speak highly enough of Kevin and Mer, the two local Belize staff working here during my stay.

Each day we take two of the small boats down to our study site, about 1km south of the station. Our team from the University of Texas and Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences is doing a range of in-water surveys for fish and habitat while I’m drone mapping. We come back to the station for lunch, and then head out again in the afternoon for more data capture. Some of the team often stay in the lab to process the fish data.

My first job on the island though was to train a partner in crime. None of my colleagues had done drone work before and it’s not a task I can do alone.

So on the first day we had some fun with two of the graduate students and the station manager! Using my She Maps protocols, I taught them how to fly and plan a simple drone mapping mission.

Then we went outside for some catch and release practice. Being able to do this safely is critical to working with drones on a boat.

Storing, processing, and managing my data

Data processing is pretty easy for me. Over lunch I just need to upload my data to GeoNadir, format my SD cards, and charge batteries and I’m good to go.

I’m the first to admit that I’m not very skilled in taking field notes. So being able to upload my data immediately before I forget what I was doing is fabulous. I know that my data (and metadata!) are then safely stored on the cloud, and the orthomosaicking process will happen while I’m capturing more data in the afternoon.

Processing in this way also makes my life easier as I don’t have to take a heavy duty processing computer into the field with me. But I can still get the processing done so that I can check to make sure I haven’t missed anything. There’s nothing worse than coming home and realising that something critical was missed in the field!

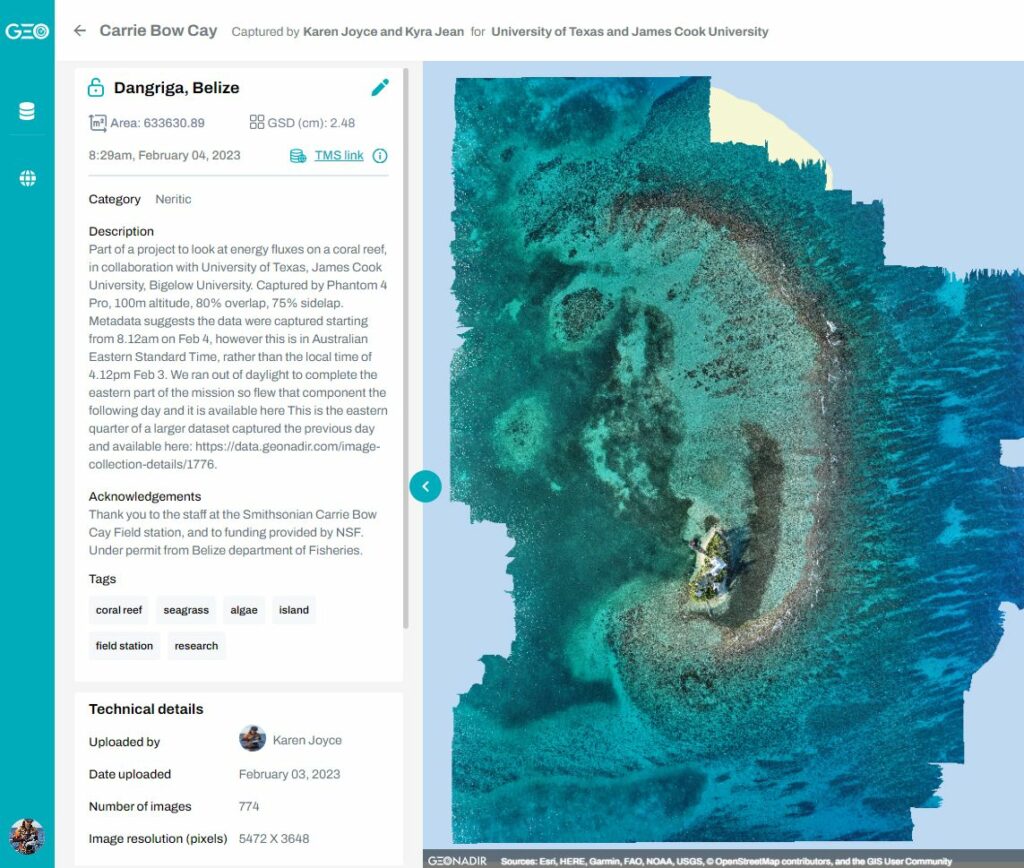

I can’t help but marvel at the resolution of drone data compared to what I can access with satellites. Freely available satellite data typically has a ground sample distance (GSD) of 10m per pixel or more.

Over coral reefs, we have access to Planet Dove data with a GSD of 5m thanks to the Allen Coral Atlas project. But at 120m altitude with a drone (legal height limit), I can achieve 3cm. The difference in detail and habitat information is outstanding.

As we are interested in looking at the habitats of individual patches of coral in this project, drones are critical.

Drone 120m altitude

Drone 120m altitude

Planet Dove satellite

Planet Dove satellite

Analysing data in the field

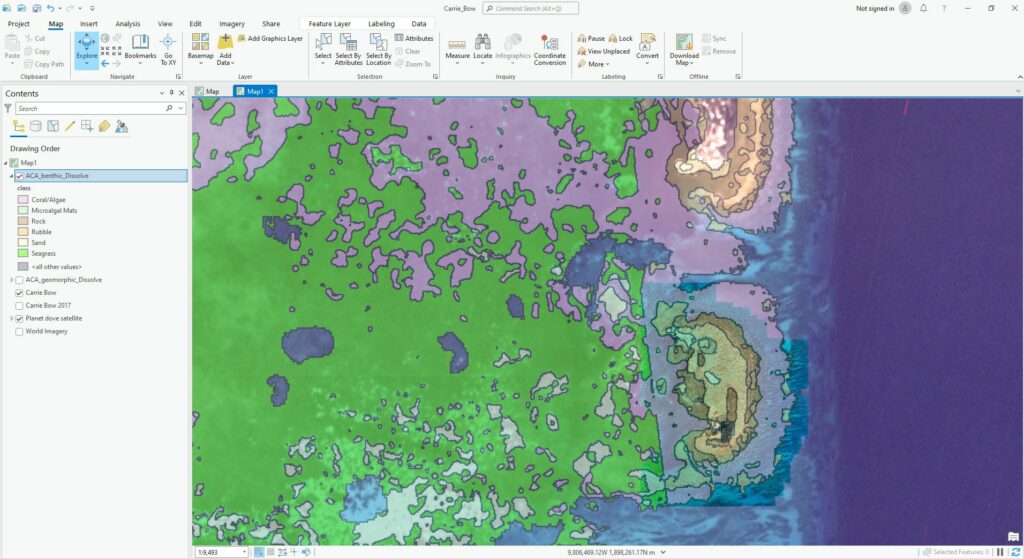

One of the nice things about GeoNadir is that I can choose to download the completed orthomosaic, or I can stream it into my GIS through the tile mapping server (see how to do that here). Viewing the data directly on the GeoNadir platform is fantastic, but being able to integrate other datasets is key to the work that I do.

As our tile server is only a new enhancement to GeoNadir, this is the first time I’ve had the joy of being able to use it like this. It’s made such a difference to the way I can quickly check and evaluate my data straight away.

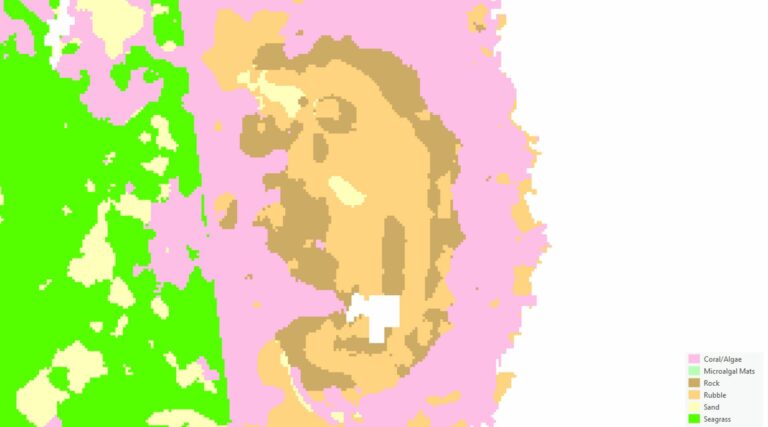

Comparing with other data

In my work, I’m really interested in seeing how we can use drone data to improve satellite data classifications. We use satellite imagery all the time to make decisions about the environments in which we live and work. But where satellite imagery is great for broad scale understanding, it lacks a lot of detail.

The Allen Coral Atlas is the first global habitat classification for coral reefs. But at a local scale, it misses the fine scale detail. And one of the biggest challenges is being able to distinguish between coral and algae. I’m hoping that we can use drone data to help.

Allen Coral Atlas habitat classification

Allen Coral Atlas habitat classification

Drone

Drone

Time series analysis

In 2017, the team from University of Central Florida Citizen Science GIS were here as part of their drone mapping missions. They’ve uploaded their data to GeoNadir as well, which means that I can access it and compare how the reef and cay looks today with how it looked five years ago.

Once again, I’m streaming these data directly into my GIS using the GeoNadir tile mapping server so that I can assess some of these changes. See if you can spot the differences below! Look closely at the island 🙂

Feb 2023

Feb 2023

Jul 2017

Jul 2017

Super easy to share

My favourite science is always done in collaboration, and this project is no exception! There are six other scientists here with me on Carrie Bow at the moment, and there are others working on the project who couldn’t be here this week. Most will need to access the drone mapping data at some point throughout the project. But I won’t need to send them a hard drive to sift through a bunch of folders. And they won’t need to wait until we get home to sort it out either. It’s there ready to go!

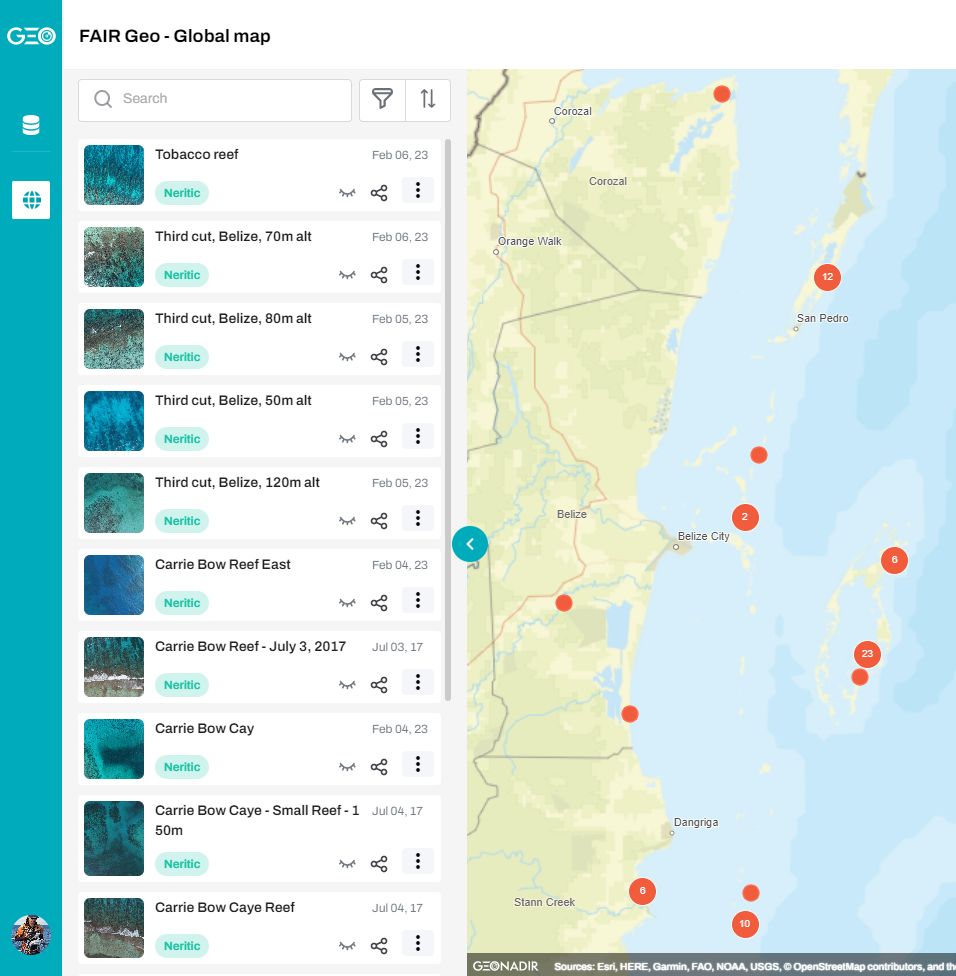

So far this trip, we have already contributed 11 datasets to mapping the region. There are 54 more that you can also check out from others who have been mapping Belize! No need to be a collaborator on the project either. Everything that you see here is FAIR – findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable.

It’s been such a privilege to see the hard work we’ve been doing over the past two years come together to make my life easier. But honestly I want more than that. I hope that my struggles and learnings have created something that will make your life easier too! So if you are someone who captures drone mapping data, wants to learn how to do it, or wants to analyse any of the many drone datasets our users have shared from around the world, I’m sure that we can help you out. There’s no better time than today to get started.

A huge massive thank you to Dr Simon Brandl from the University of Texas for inviting me to be a part of this project; Kyra Jean Cipolla for being my trusty drone catcher and co-pilot; the US National Science Foundation for funding the research; Kevin and Mer for being the fabulous station staff keeping everything well organised and all of us incredibly well-fed; and Dr Doug Rasher for being our boat captain.

You can check out all of the drone mapping datasets I’ve captured here. I’ve also added a couple of videos below to show how easy it is to upload data and stream to your favourite GIS application.