As a relatively new technology, it’s common for people to come to the world of drones from different backgrounds. For Joan Li, drones and deep learning gave her the chance to explore her passion for marine science when the pandemic meant she could no longer observe it from below the water.

As the Earth Observation Data Scientist for GeoNadir, she gets to use what she’s learned to help improve the way datasets are processed on the platform.

From diving to drones

Joan’s love of diving drew her to the world of marine science. She’s volunteered and worked for a range of organisations, diving to conserve, learn from, and teach about the marine environment. But more than just being a dive pro, Joan wanted to learn the science behind the world beneath the waves.

She decided to study a Masters of Marine Science at James Cook University (JCU), Australia. But, like many people, Joan’s study plans were thrown by the COVID-19 pandemic. Restrictions meant diving was suddenly off the table.

“You know, covid hits. So no more in water activities. So I think: What can I do and explore with some new tools?” Joan said.

“Remote sensing and GIS just opens up this whole new field.”

She reached out to Dr Karen Joyce to find a project to develop her GIS and remote sensing skills.

Karen is a GIS lecturer at JCU and co-founder of GeoNadir. She’s done a lot of work mapping coral cover on the Great Barrier Reef with drones. But looking over old datasets, she quickly realised they were useful for learning about more than just coral. You could also see sea cucumbers in the drone images.

While not the most charismatic of creatures, sea cucumbers play an important role in nutrient cycling on coral reefs. They’re also a key fisheries species. But there isn’t very much information on their population size or distribution, which makes sustainably managing the fishery a challenge.

Taking inspiration from Karen’s old datasets, Joan adapted an object detection algorithm to identify and count sea cucumbers in drone images. The goal was to support efforts by the Great Barrier Reef foundation to understand sea cucumber distribution.

Joan on a dive on the Great Barrier Reef. Photo credit: Harriet Spark

Joan and Karen on a mapping mission on the Great Barrier Reef. Photo credit: Harriet Spark

Working as GeoNadir’s data scientist

While Joan continues to collaborate on the sea cucumber project, as GeoNadir’s Data Scientist, she uses the skills she’s learned to find better ways to process and analyse user’s drone mapping data.

Normally, the raw images that come from drone mapping data require some level of manual processing to create orthomosaics. Joan is exploring how to streamline this process to quickly create high quality orthomosaics from user’s data.

“So my part is trying to build up and optimise automatic pipelines to make this orthomosaic processing step easier, especially for people who have no geospatial background. Photogrammetry softwares usually provides a default setting that might not fit all scenarios, but one also may not have all the time in the world to tweak and explore different settings and learn what each step means in photogrammetry. We are hoping to provide a pathway that our users might find easy to start with.” Joan said.

“For example, we’re still testing how to cope with very large data sets, and this is usually a struggle because your computer is limited. We need to see whether there are either cloud computing or other parallel computational sources we can bring in to accelerate the process,” she said.

Analysing drone data

Joan isn’t just aiming to improve the processing of datasets. She’s also looking for opportunities to improve capabilities to analyse drone data.

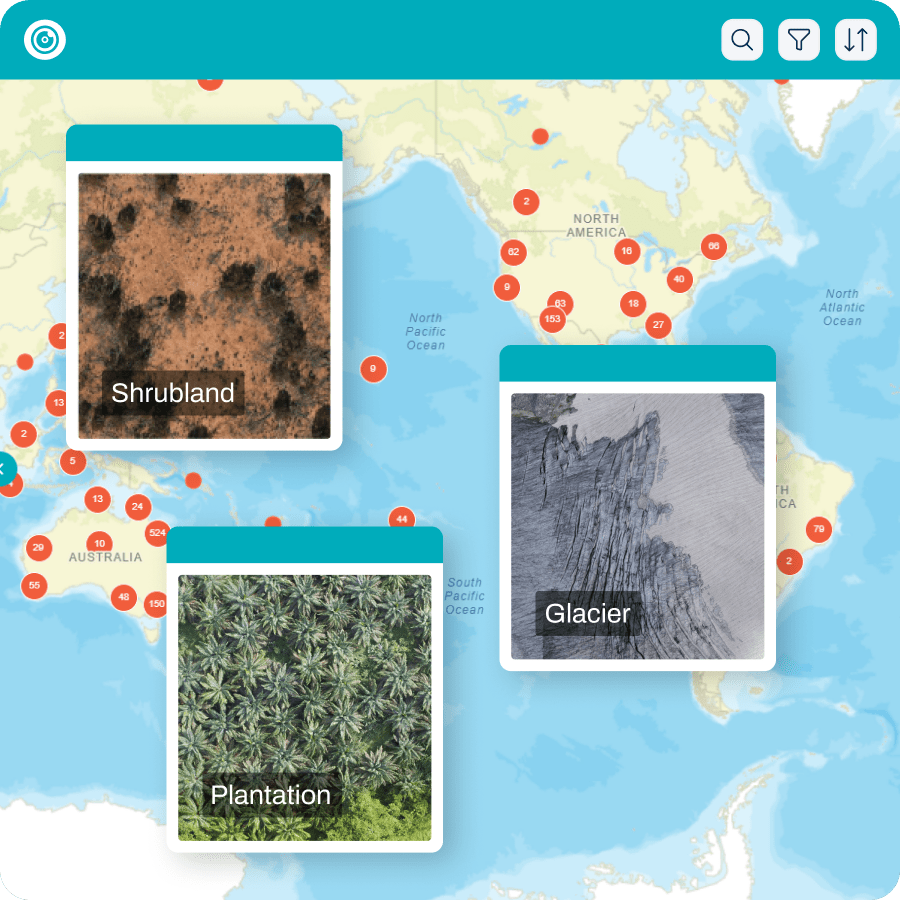

“We’ve got all this data from different habitats and different environments. What is the valuable information that is out there that we can help to analytically extract? Instead of just providing it as a base map, we’re also providing knowledge.” Joan said.

It’s no small challenge, since even in the same datasets, users might be looking for very different information.

“Users will have a million questions for all these datasets. Some would like to see shallow water coral conditions. Some would like to see coastline erosions, even though the knowledge is from the same datasets,” she said.

It’s the ability to extract so much information from one dataset that makes drone mapping data so valuable. Joan says it’s important people know how much drone data is already out there, available to use.

“We’re already in such a data-overwhelmed world,” Joan said.

“For people who are collecting data, you might be collecting something that can be useful for other people; for other people who use data, you never know what is out there that can be useful for you,” she said.

“It’s just like going to thrift stores, it doesn’t matter if you’re buying or trying to get rid of something that is no longer needed, you’ll be surprised how much value is in there. Up-cycling is a term used a lot in the conservation field and there is a lot of data that we can up-cycle as well.”

The value of drone data

GeoNadir aims to create a platform where up-cycling drone mapping data is as simple as uploading a dataset. In her role, it’s easy for Joan to see the value of the data that users upload to the platform.

“I think for me, the most important part at this stage is about making diverse raw data readily available . Technology is always improving, but time also continues. All the snapshots that we are taking at this moment provide unique information,” Joan said.

“Every part of the earth is valuable. And there are so many details, things that we’re not aware of… but in your image, there will always be something there that you cannot see. But… with some sort of analysis and manipulation, it will become useful.”

Connect with the GeoNadir team

Curious about drone data processing? Don’t hesitate to reach out to Joan and the rest of the GeoNadir team. Your feedback, ideas, and experiences helps us make the platform better for everyone, and we love being inspired by the work that you do with drones!